Has AI Solved Materials Discovery? - AI & Materials Discovery Part 2

Welcome to Part 2 of our look into AI and Materials Discovery. If you haven’t yet, take a look at Part 1, where we dive into the most prominent approaches to AI-driven materials discovery for helpful context.

To answer the question of if advances in AI around foundational model improvements, increased reasoning capabilities, and of course, unprecedented computational power have fundamentally changed what’s possible in materials science, we’ll need to look beyond the claims of the companies raising money in the space. We need to scrutinize what has actually changed for the better, and what remains as it has been. And from there, we’ll look at what this all could mean from the investment perspective.

Has AI “Solved” Materials Discovery?

The Good: Foundational Models

A quick search online yields some compelling claims from companies in this space: Eonix states their platform is "37x faster and 16x cheaper than traditional R&D," while Dunia aims to reduce development timelines "from decades to under three years”. Similar searches around hardware-enabled companies generally announce in various terms that their solutions enable the ability to more rapidly handle, interpret and learn from internally generated data.

These claims are not unfounded. Real and substantial technical progress in AI has been made in the last 5 years. Foundational models, evolved from training on vast datasets, have been adapted to scientific literature and IP databases. They can now reason across chemistry, physics, and material science in ways previously unattainable. Powerful models can work through multi-step scientific problems, while improved predictive algorithms have enhanced accuracy in searching chemical space and suggesting promising candidates. Initial screening phases are now far more efficient, and the sophistication and speed of autonomous labs and robotics is such that they can run orders of magnitude more experiments than previous generations.

The Unchanged: The Simulation-to-Reality Gap

Despite massive improvements in AI capabilities, there are some crucial limitations that can’t be ignored.

Today’s AI models accelerate computational simulations, but they do not replace them with fundamentally different physics models. Established computational frameworks for predicting material properties, like density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics, continue to face very real (and equally well-known) accuracy limitations, especially when applied to complex, real-world conditions.

The "synthesizability" problem exemplifies this challenge. AI can predict steady-state materials that are theoretically optimal but practically impossible to manufacture, or that require exotic synthetic pathways incompatible with industrial production. Modeling factors that are inherent to synthesis pathways (such as transition states, electron transfer reactions, electrochemistry, multi-component systems, or multi-phasic interfaces) are limited to rough approximations even with the most advanced simulation technology today. Because of this, things like yield, reproducibility, and stability in real world conditions remain largely unknown before a material is actually synthesized.

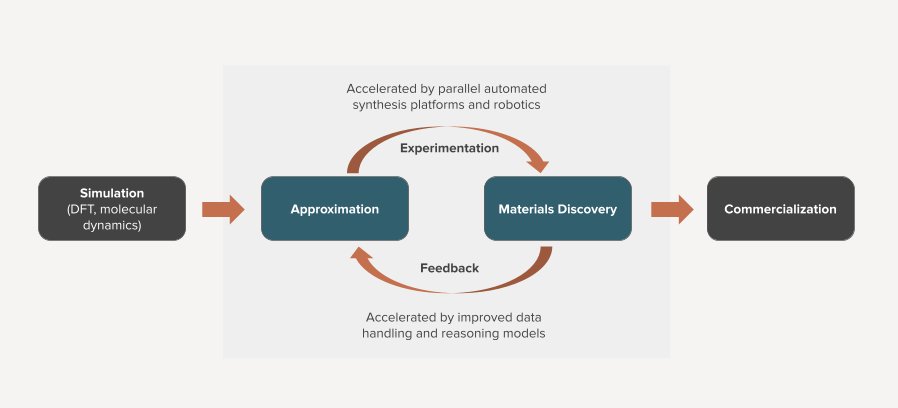

Most companies leveraging AI for materials discovery are not addressing this core limitation. Instead, they are using massively accelerated machine learning coupled with high throughput experimentation to uncover more chemical space and patterns of data that allow for more robust suggestions of promising candidates much faster than before (Figure 1). It is a brute-force approach, rather than an improvement in the prediction models themselves. These limitations mean that even with vastly improved AI, extensive physical validation remains essential.

Figure 1. Today’s AI and automated synthesis platforms massively accelerates the time between approximation and materials discovery. It does not improve the accuracy or power of fundamental physics-based prediction tools, or the time to go from discovery to commercialization.

The Opportunity:

With all of the above in mind, the way to truly uncover practical new materials is to run as many experiments as possible, and test these materials in a relevant environment. AI can guide the direction for these experiments and accelerate experimental design, but in most cases it will not completely eliminate the need for them. This need is even more profound within fields where the fundamental material physics is poorly understood, like room temperature superconductors or electrochemical catalysis .

The unprecedented scale of experimentation planned by the companies in this space could conceivably generate a competitive advantage. The sheer volume of experiments may generate unique insights from fully networked, well-structured and previously unobtainable data, and the funding some startups have obtained (and are seeking) might even provide enough runway to prove this approach can work. Opportunities are there, so long as innovators remember that as much as AI has changed, fundamental physics has not.

The Venture Perspective

For an opportunity to be considered a viable venture investment, there must be clear competitive advantages that will capture significant portions of big markets while delivering a strong return within the lifetime of a fund. This principle remains unchanged, or perhaps more important, when considering AI materials discovery companies whose path from technical capability to value capture is unproven.

Software vs Platform: Extremes of Risk and Reward

Software-only materials discovery companies offer the quickest way to revenue, but their competitive edge is usually thin unless they're fundamentally improving the underlying physics (which is extremely hard and takes a ton of resources). The winners here will probably be those who either totally dominate the market by keeping customers happy and engaged (think Schrödinger) or those who come up with truly new computational methods that others can't copy. The problem is, though, that if they can't move past just offering services, their long-term value for investors is capped.

Moonshot bets on truly game-changing materials are the complete opposite and a different kind of investment profile. These could be huge for entire ecosystems and might even lead to breakthroughs that justify mind-blowing valuations. Room temperature superconductors, for example, could be worth trillions. But with seed rounds hitting $300-500M and pre-revenue valuations over $1B, only the investors with the deepest pockets and the highest tolerance for risk can even play. The probability of these companies actually delivering a return is pretty slim.

Platform vs Product: Value Capture Determines Venture Returns

Hardware-enabled AI for materials discovery can be a more attractive investment, but should be evaluated on their market choice and team, not just how powerful their discovery platform is. While the platform's technical sophistication matters, the main thing is whether the team can actually commercialize materials in their chosen market. Smaller startups raising less than $20M will almost certainly have to choose between becoming a product-focused materials company or continuing to build out their platform. The first option requires a completely different skillset that founding teams dominated by computational scientists usually don't have. The second option needs ongoing capital to fund platform development while still facing the same monetization problems that hurt earlier generations.

This situation has some big implications for early-stage investors. If these companies get acquired, the valuation will be based on the value of specific materials or products to the buyer, not the discovery platform itself. Buyers will pay for proven, de-risked materials with a clear path to market, not the mere promise of future discoveries.

Investment Framework

For investors evaluating hardware-enabled AI materials discovery companies, the following framework prioritizes the factors that can truly drive venture returns:

Market value creation potential. Does the end product represent a genuine breakthrough or merely an incremental improvement? Investors should stress-test claims of disruption by examining existing solutions and understanding whether the new material solves a problem worth paying for, or simply offers marginal improvements.

Technology readiness and commercialization risk. Does entry point valuation truly reflect how far the company has progressed down the commercialization path of their chosen material or product? The valuation should reflect the compounded risks of synthesis scale-up, performance validation, regulatory approval, and market acceptance, and not the stage of the discovery platform.

Team composition and market expertise. Does the founding team's background match their chosen vertical? Investors should evaluate whether the team has direct experience in their target market, meaningful relationships with potential customers and partners, and a realistic understanding of the path from lab to commercial scale.

Strategic partnership quality and validation. Do showcased partnerships signal market credibility, and are their partners committed beyond R&D testing? The strongest startups can secure partnerships where customers are co-invested in success, not just sampling materials with minimal commitment.

Value capture requirements and vertical integration. How vertically integrated does a company need to be to capture outsized value, and what implications does this have on capital requirements? Companies that underestimate their required vertical integration typically face either value leakage to manufacturing partners, or expensive pivots to build capabilities they initially outsourced.

Exit landscape and acquirer motivations. Do the exit dynamics of a chosen market point to the potential for a venture scale return? The appetite for an upstream industrial chemicals company to pay a high technology multiple is very different to that of, say, a game-changing semiconductor technology.

Conclusion

AI is clearly speeding up materials discovery, making timelines shorter and expanding the chemical space exploration. But having faster simulations and automated labs isn't enough; the real value comes from commercializing, scaling up, and integrating vertically. The companies that win will be materials companies that treat AI as a tool to support a sustainable business model, not as a replacement for one. For investors, the biggest returns aren't in AI for the sake of it, but in the teams and markets that can actually turn a discovery into a real product and a long-term, defensible business.

The content provided in this blog post is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice, financial advice, or a recommendation to buy or sell any securities or financial instruments. No information herein should be relied upon as a substitute for professional investment advice tailored to your individual or corporate circumstances. Always consult with a qualified financial advisor or other professional before making any investment decisions. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Past performance is not indicative of future results.